Athletes struggle to find purpose, identity after sports

Liz Henderson | January 5, 2020

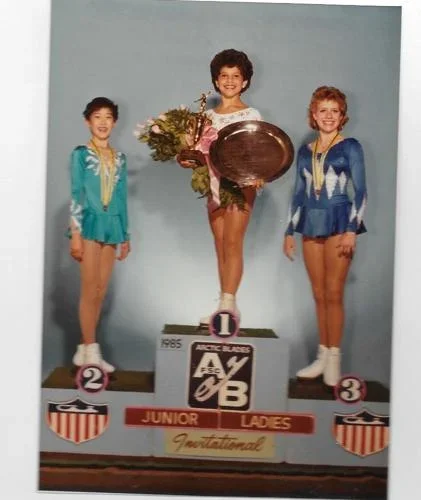

Olympic figure skating hopeful Val Jones saw her future ripped away in the split second it took for the ligaments in her knee to snap.

With a single misstep on the ice two weeks before her 18th birthday, more than a decade of training and singular focus became a blur of uncertainty: Would she ever compete again? And if not, who was she?

After months of rehabilitation, doctors told Jones she was lucky she could still walk.

Deep in a “spiraling, self-destructive mode,” Jones sat in her California bedroom in the late 1980s, where she had lined up five bottles containing an assortment of powerful sleeping pills. Without her sport, the only thing she knew with absolute clarity was that she wanted to die.

“Everything I had ever dreamed of from the time I was 5, in a second, was gone. Everything,” Jones told The Gazette. “I was just so tired of being sad and overwhelmed and I just wanted the pain to go away. I just thought, ‘I can’t do this anymore. I can’t live this life anymore.’”

Athletes forced to leave their sports, through injury, graduation or retirement, routinely battle depression and anxiety. It affects elites and amateurs of all ages, across the spectrum of sport, gender and competitiveness.

It’s a crisis hidden beneath a facade of strength and drowned out by the roar of the crowds.

No other place in society glorifies perfection — and suffering — like sports.

“When I first heard the term ‘mental health,’” former Denver Broncos wide receiver Brandon Marshall wrote in an online memoir, “the first thing that came to mind was mental toughness. Masking pain. Hiding it. Keeping it inside. That had been embedded in me since I was a kid. Never show weakness. Suck it up. Play through it. Live through it.”

Athletic culture heralds pain as a rite of passage. The greatest part of an athlete’s career narrative isn’t them crossing the finish line — it’s Hercules' journey to the underworld and back, the extra push that takes a potential hero from ordinary to extraordinary. Athletes know it as the grind.

But painting athletes in a gilded, glossy finish muddies the line between the grind and challenges with mental health — for players, coaches and even parents. The hurdles athletes face can take on a new scope when traumatic injury, age, or other unavoidable factors threaten, or end, lifelong pursuits.

At a 2018 panel, Michael Phelps, the most successful Olympian of all time, recounted the words he said to his wife after his retirement:

“I feel like I’m failing in everything that I do.”

From injury to depression

The relationship between depression and sports is a complicated one.

Doctors recommend that to combat depression and anxiety, individuals should exercise at least three times a week, practice good nutrition, sleep at least eight hours and surround themselves with a support system. Even amateur athletes are exceeding these conditions by far, yet a number of high-profile, highly successful athletes have taken their own lives in recent years:

• In June, professional beach volleyball player Eric Zaun jumped to his death from the 29th floor of his Atlantic City hotel room. He was 25.

• In March, 23-year-old Olympic cyclist Kelly Catlin killed herself months after suffering a concussion.

• In January 2018, 21-year-old Washington State University football player Tyler Hilinski shot himself after suffering from early stages of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease linked to head trauma.

Suicide remains the third leading cause of death for athletes, according to the Indiana Law Journal. A 2016 study by researchers at Drexel and Kean universities found that nearly 25% of collegiate athletes have reported symptoms of depression.

Experts say the dynamics of modern sports provide an especially dangerous landscape that fails to prepare athletes for long-term physical and psychological health.

Players are often pushed beyond their limits to recover from injury as quickly as possible. An athlete who misses even a few games because of an injury can lose a starting position. The pressure to recover leads many athletes to experience chronic pain, which researchers say can make them especially susceptible to depression.

“For someone who’s coming off an injury, or is predisposed to an injury, you can develop chronic injuries,” said Tim Neal, who co-authored the NCAA’s “Mind, Body and Sport” publication and has been instrumental in developing mental health guidelines in college sports. “Studies are showing, by and large, that whenever you’re dealing in chronic pain, that has an effect on your emotional and mental well-being.”

When the pain is too excruciating to push through, athletes can face derisive peers. Jones, who skated with Kristi Yamaguchi, Brian Boitano and Tonya Harding, found that leaving a sport, no matter what reason, is heresy.

“I can remember seeing my friends later and them saying, ‘Oh we heard you quit,’” Jones remembered. “I didn’t quit. I didn’t quit because it got hard — I quit because the pain was no longer manageable.”

BY THE NUMBERS

30%: undergraduate students who reported feeling so depressed that they could barely function.

6.3%: collegiate student-athletes who met the criteria in 2016 of clinically significant depression.

21%: student-athletes who experienced psychological concerns, particularly depression, and reported high alcohol abuse while in school.

11%: high school athletes who will have used narcotic pain relievers like OxyContin and Vicodin for non-medicinal purposes by the time they’re seniors.

45%: male team-sport athletes who report having anxiety and depression.

79%: collegiate athletes who report less than 8 hours of sleep per night in season.

64%: Olympians who report significant insomnia symptoms.

7.3%: elite student-athlete deaths that are by suicide

60%: female athletes who report body shaming pressures from coaches

Sport as identity

For the talented and devoted, sports can be a full-time job.

A 2018 study in the Journal of Amateur Sport found that NCAA Division I student-athletes spend up to 40 hours a week on sports, twice the weekly hours mandated for participation by the NCAA. Nearly 12 hours of the average student-athlete’s day is comprised of sport and school, the study found. It’s common for athletes from high school to the Olympics to miss out on family events, vacations and holidays.

And demands on student athletes are higher than ever.

Even though the NCAA has recently tried to tighten recruiting rules, the organization’s research shows that early recruiting has been especially ubiquitous in the past decade. Once competing in college, players are reporting higher levels of sleep loss, mood swings, decreased self-confidence and inability to concentrate than their nonstudent-athlete counterparts, the same study found.

“When I first got into athletic training, (the trainer) saw them during the preseason, during the season and when the season was over it was ‘We’ll see you next preseason,” Neal said. “There was no summer training, there was no heavy off-season conditioning. The athletes are now in year-round conditioning.”

And life after sports can be just as grueling.

“Football becomes your identity,” wrote George Koonce, a former NFL player who attempted suicide, in an ESPN column. “Your family buys into it, your friends buy into it, the alums from your college buy into it. And then it is gone. You are gone.”

Johnathan Franklin, a running back, was drafted by the Green Bay Packers in the fourth round in 2013. He thought he’d be on the gridiron “forever.”

Only 12 games into the season, he caught a pass that put his helmet in the direct path of an opponent’s. He fumbled the ball, and all he could think of was scrambling to get it back. But his legs wouldn’t move.

A medical scan showed a spinal contusion. He continued to train that off-season, determined that a little black spot on his medical scan wouldn’t stop him from competing. But by the time the next season came around, he was forced from the game he loved.

The week he retired, Franklin was on a plane flying to his then-girlfriend’s graduation. He hadn’t told any of his family or friends that he was no longer able to play football.

“I remember sitting downstairs because I had people over at my house,” Franklin told The Gazette. “I tweeted it out before I said anything. And I went upstairs, and I just started crying. It was like, ‘Wow, this is a reality. I can never play football again.’ It was a sense of depression, like, ‘What now?’”

In recent years, the National Football League has been under increasing public pressure to address the onslaught of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. The CTE Center at Boston University published a study in the medical journal Annals of Neurology that found football players doubled their risk of developing CTE for each 5.3 years they played.

CTE and its related-suicides have forced sports organizations at every level to discuss sports injury, cognitive impairment and mental health.

Unprepared for the post-sports life

The NCAA touted in one report that 56% of its former athletes are thriving after sports. It sounds good until one considers that that leaves 44% struggling to find purpose post-sport.

“There is a focus on excellence and moving up the so-called pyramid, and focusing on your physical skills and developing those physical skills, to the exclusion of other things in life,” University of Colorado at Colorado Springs professor Jay Coakley said. He’s studied athletes from a sociological perspective, and moderated a U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee panel this year that touched on the idea that anything to do with sport is pure and good — the Great Sport Myth, as he calls it.

“So many athletes are used to internally processing and sucking it up when experiencing personal adversity,” said Christine Pinalto, executive director at Sidelined USA, an organization dedicated to helping athletes transition following a medically-forced exit from sport. “When it comes to the mental part of it, they're used to not expressing weakness. Because to them, that's a failure on their part to ‘handle things.’”

Few Olympians are equipped to deal with the real world after spending a lifetime competing, said Eli Bremer, a former USA Pentathlon athlete and member of USOPC's Athletes' Advisory Council. Not only are many making below minimum wage in stipends while they compete, he said, but they are also stunted, from a maturity standpoint, and less capable of transitioning into a livable career.

Living off a low income, identifying only as an athlete and feeling unprepared for life after sport can be a recipe for mental health challenges in Olympic athletes, Bremer said.

“The mental illness is a symptom of an unhealthy system,” Bremer said. “It's really unbelievable to believe that we're going to birth out athletes that are happy, well-adjusted, productive, and mentally in a good place, when they spend years if not decades in a system that subjugates them and keeps them in a bad place. You have to deal with the higher-level problem.”

He's pushing reforms that give athletes more say on the Olympic Committee.

'Like a second instant death'

With thousands of athletes graduating each year, hundreds more medically retiring and others finishing their final Olympic run, the identity crisis they can go through leaving a sport has remained one of the best kept secrets in sport culture. The struggle has become so widespread, not just in athletes, that researchers have given it a name: "Identity foreclosure."

It’s the psychological equivalent of losing a loved one, but very few know a healthy way to grieve it.

For Jones, who lost her dad and her skating identity in the space of a few years in her teens, the experiences felt almost identical.

“It was like a second instant death," recalled Jones, now 50 and living in Parker with her husband and two children.

Sitting in that dark California bedroom decades ago, she realized something. All she had to do, she said, was go to bed. Though depression doesn't ever feel that simple, for Jones, it was like a restart button. But more than that, it was the simplest method for her to stay alive.

"That day with those five bottles in front of me I had to really dig deep," she remembered. "I had to think about what my dad would do. What would he tell me if he was here right now?... I kind of felt him saying 'I just need you to keep fighting.' And so I kept fighting."

Parents and coaches have their identity wrapped up in sport, too, and those pressures and emotions can play into the fallout when a trajectory doesn’t go as planned. And that can heap even more pressure on the athlete.

“The parental moral worth is tied to the success of their kids and how much they dedicate themselves to nurturing their children's dreams,” UCCS' Coakley said.

The pressure to maintain an outwardly “perfect life” can keep many athletes in silence. Training tells them to push through and pushing through means shutting up.

“I think, sometimes even in this culture, and in America, we're afraid of going through the grief process because no one really wants to talk about that,” Sidelined's Pinalto said. “It's a very uncomfortable position to be in to just throw it out there that ‘I'm deeply struggling.’ That's just not something you're going to throw out in conversation. Where is the landing pad for that? And that's the big question I think athletes have is, ‘Who would I even talk to about this?’”

Setting athletes up to fail

Many athletes don’t have a clue how to face depression.

In 2013, the NCAA’s chief medical officer, Brian Hainline, declared mental health the No. 1 health and safety concern of the NCAA. The next year, the NCAA’s research arm, the Sports Science Institute, published “Mind, Body, Sport," which Hainline described to The Gazette as "not a great success." In 2016, the Institute published “Mental Health Best Practices,” a guide for programs to follow in terms of supporting their athletes.

The guidelines prompted several mental health initiatives, including a task force that sought to put the guidelines into operation at the organization's 1,100 member schools and a seven-hour long instructional video for how schools can personalize the guidelines.

“If you look at colleges across the country and you talk to university presidents, they’ll uniformly tell you that mental health is our biggest issue," Hainline said. "That’s what keeps them up at night. We live in a country, the United States of America, which marginalizes mental health. You look at almost every health insurance plan and we don’t support mental health properly.”

It wasn’t until 2019 — six years after mental health was declared the No. 1 priority — that the Power Five Conferences unanimously voted at the NCAA Convention to require mental health services for athletes.

That year, the Atlantic Coast Conference held its first mental health and wellness summit, and the Pac-12 Conference announced it will continue to fund its mental health task force to address student-athlete head trauma, mental health and injury prevention.

“Mental health is still in our country under-recognized, under-managed, under-budgeted," Hainline said. "It’s really problematic. We’re trying to offer up athletics as a subculture … for changing the culture of society as it has to do with mental health.”

Hainline said the national office has “100% supported” all that’s been done in terms of mental health research. The question now, he said, is whether it will move into an enforcement phase, which he admits is tricky in mental health.

“What do you enforce?" he questioned. "I don’t even know the answers to those questions yet. But I think the primary role is to help the schools get ahead of society. To that degree, so far there hasn’t been one iota of resistance. It’s been nothing but support.”

Still, some student athletes have remained largely critical of the NCAA.

The organization has a research branch that directly influences policy decisions based on its data. But it doesn't track suicide among college athletes. It doesn't know whether its athletes even utilize mental health services while competing.

But addressing mental wellness has caught the attention of other organizations, too.

The International Olympic Committee invited Hainline in 2017 to co-chair the first-ever consensus meeting on mental health for elite athletes. It led to a 33-page report published in June by the British Journal of Sports Medicine that sought to address the chasm between athlete physical health and mental health.

Some U.S. Olympians have also become more vocal about the challenges they’ve faced, including issues with mental health.

Last year, the USOPC funded the Borders Commission, an internal review process meant to examine what had gone so wrong inside the organization that allowed the USA Gymnastics' sexual assault scandal perpetrated by team doctor Larry Nassar.

During the course of this investigation, the commission heard that many former athletes suffered from mental anguish after their careers ended and found little help from the USOPC.

“The USOPC must assume its rightful leadership position by setting the standard for protecting athletes,” the commission’s 58-page report read.

Rightful leadership means being more athlete-centric, says Bremer, one of the two modern pentathlon representatives on the USOPC’s Athletes' Advisory Council.

“Mental health services are a critically important component of the resources that the USOPC provides to ensure athletes have the support they need," wrote USOPC spokesperson Mark Jones in an email to The Gazette. "As part of our most expansive governance reform in nearly two decades, we recently updated our mission to ensure that sustained well-being for our athletes, along with competitive success, is at the forefront of everything we do."

The Committee transferred the chief medical officer position and the sports medicine operation from the high performance team to the athlete services team to ensure health care services are focused on wellness, he added.

"Like all sectors of society," Jones wrote, "the USOPC continues to learn how best to help address the mental health crisis in our country and we welcome feedback from athletes and others on how we can be even better.”

Last year, a study from the University of Colorado’s Sports Governance Center found that all but one of 22 sports federations under the USOPC were graded D's and F's for a lack of democratic practices and a lack of checks and balances to keep athletes safe.

Bremer cast doubt on on the USOPC’s mission to support its athletes, saying it's a system that sets athletes up to fail.

“(To the USOPC,) an athlete is a person who — the best-case scenario is — behaves themself, they win a gold medal,” Bremer said. “They shut up and they ride off into the sunset.”

Crippling panic attacks

Many find that riding off into the sunset is nothing more than an empty euphemism.

Vail-born Katie Uhlaender, 35, is one of the most successful skeleton athletes in the world. She’s won six medals at the International Bobsleigh & Skeleton Federation World Championships and competed in four Olympics.

Two years ago, Uhlaender discovered her best friend, three-time Olympic medalist bobsledder Steven Holcomb, dead at the Olympic Training Center in Lake Placid, N.Y.

It was unusual for Holcomb not to answer her text messages. She went to his room to check on him. Pounding on his door for several minutes, Uhlaender finally asked a housekeeper to let her inside.

Holcomb was prone, and didn't appear to be breathing. Uhlaender turned away to tell the staff member to call 911.

But even in that instant, she knew. As she turned back to Holcomb, she felt cloaked by a blanket of hopelessness. There was nothing that she or anyone else could do. The moment for helping her friend had passed.

As she tells it now, that sense of helplessness marked the beginning of trauma in her own life.

Holcomb’s official cause of death was a lethal combination of a prescription sleeping aids and alcohol.

But Uhlaender felt that she knew him better. He died of escapism, she said, questioning if his 20-year-career meant anything.

“I think there are a lot of pressures," Uhlaender told The Gazette, and part of that is "wondering if we’re wasting our lives. … I’m not coming out of my career with a lot of money. I don’t have a lot of work experience. The society (at large) is different. It’s a lot of pressure, and it’s confusing.”

Uhlaender lived off a monthly stipend of about $1,250 while she competed in the Olympics. Today, while she trains for her fifth Olympic appearance, she receives no stipend at all. Most of what she's saved goes toward paying to compete. Athlete stipends are determined by the USOPC, Uhlaender said.

After Holcomb’s death, she suffered from crippling panic attacks that gradually worsened from insomnia. She was given a chance to work with a sports-psychologist to help her to perform, but not to deal with the grief of losing a friend.

“He told me I seemed to perform ‘better from a dark place,’” she recalls with a trace of disbelief. “I felt like it was my duty to just focus on competition and to just do what I needed to do.”

She’s since learned from therapy that she, in fact, did not compete better from despair. Being relaxed is key to bobsledding, and tensing up from symptoms of post-traumatic stress slowed her down.

'Recognizing what's abnormal'

Given the rise of youth suicide nationally, experts want to better address the stigma of behavioral health problems among athletes. Tim Neal, who's helped advocate for mental health guidelines at colleges, believes athletic trainers are one key to building a bulwark against suicide.

“The athletic trainer has a unique place in sports, because the athletic trainers are with and assisting the athlete during their worst moments,” Neal said. “People equate that worst moment to a physical injury. It could be a life-threatening injury, career-ending injury, a season-ending injury. But more and more, we are dealing with more mental and behavioral health problems being that athlete’s worst moment.”

Ron Courson, the director of sports medicine at the University of Georgia, led a panel at the 2019 National Athletic Trainer’s Association convention addressing student-athlete mental health.

“We have a slogan here for mental health,” Courson said. “Recognize, react, refer. … I don’t want my (athletic trainers) to be a sports psychologist or a clinical counselor or social worker. But what I do want them to do is be able to recognize somebody who may be in crisis, or may potentially have some warning signs.”

Sports psychology has long been focused on performance, not mental health. There’s a serious shortage of those licensed to help with mental health issues in the athletic community, Neal said, and that responsibility is naturally falling to athletic trainers.

And even though it’s not the way it’s supposed to work, Courson says preparing athletic trainers to recognize mental health issues and to refer athletes to care could be a first step.

“If you know what’s normal for them, then you can recognize what’s abnormal,” he said. Courson is recommending that athletic programs implement mental baseline testing at the beginning of each season, similar to how trainers test for concussions.

It's something that the NCAA's Hainline agrees with, and says the organization is currently working on. He's hoping that by June, the NCAA will roll out a similar baseline test for mental health issues. It will be the first-ever sports mental health assessment tool and recognition tool, he said.

“We didn’t reinvent the wheel," said Hainline. "We took existing screening tools but then we developed a unique algorithm for how could this be applied to athletes who really are different in many ways than nonathletes.”

After retiring from professional football, Johnathan Franklin was hired by Notre Dame to mentor student-athletes on issues of mental health vulnerability. He now works for the Los Angeles Rams doing similar work with NFL players.

“One of my roles is speaking on behalf of our organization and sharing my story,” he said. “But if I didn't know what vulnerability was, if I wasn’t challenged to meet people every day in college, if I wasn’t an athlete, I wouldn't be able to do what I do every day. Even the brokenness of finding my identity outside of sports, and knowing that I'm more than an athlete, it's been a blessing in disguise.”

“Honestly, it can take years to establish a healthier self-identity,” echoed former Oakland Raiders and Tennessee Titans wide receiver Jonathan Orr, who founded Athlete Transition Services, a company that helps players prepare for life after sports.

“Athletes are aware that one day their sport will come to an end, and that's a change,” Orr said. “Everybody knows that change is going to happen. But very seldom are athletes aware of the transition that happens to you as a result of that change.”

Struggling with an ending

Many athletes will continue to struggle in silence, the departure from the essence of their lives leaving them hollowed.

On a cold December day, a recent graduate of University of Colorado at Colorado Springs talked about her life as a runner, one that took her to two national championships. It was a life that introduced her to friends and provided structure. But it felt as if it was someone else's life now — one that remained in the past.

She is struggling with the fact that her track career is over.

“I definitely don’t think everyone talks about it," she confided in a Gazette reporter, while asking that her name be withheld. "I think once you’ve become an alumni and you have your year out you think you’ll get over it. But I’m in it right now, and I’m really struggling.”

When she was in school, and someone asked her who she was and what she did, her response was always the same: “I run at UCCS cross country and track.

“Then this year," she said, someone will ask, "‘Tell me about yourself.’”

Sitting inside a coffee shop, surrounded by people, her eyes still express a loneliness. But the words don't come.